The red line shows the route takebn by an Italian soldier crossing

Albania in 1941 during Mussolini's invasion of Greece

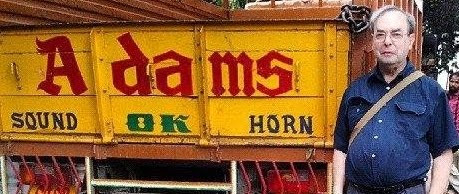

Having been successively occupied by The Ottomans (for several centuries), the Italians and then the Germans, it is not at all surprising that the traditionally hospitable Albanians became somewhat suspicious of foreigners by the end of the Second World War. This xenophobia , which was exploited by Albania's dictator Enver Hoxha, led to Albania adopting an isolationist approach rivalled only by countries like Mongolia (until recently) and North Korea (still today). The following is a brief introduction to Adam Yamey's new book Albania on my Mind. It includes quotes from the book.

When I became a dentist in 1982,

the idea of ever treating a patient from Albania

would have seemed almost as unlikely as meeting someone from Mongolia . Both

were places that hardly anyone visited from the West, and from which visitors

to the West were few and far between. Well, 30 years later, everything has

changed. Almost daily I treat Mongolians and Albanians (both from Albania itself

and also from Kosovo). Whilst I have never set foot in Mongolia , I have visited Albania .

I visited the country in 1984 when

it was even more isolated from the rest of the world than North Korea is

today. In those days, Albania

was firmly under the control of Enver Hoxha, a dictator who counted Josef

Stalin as his friend and inspirer.

Occasionally, when chatting to my

patients from Albania

(in English), I relate curious incidents that I recall from my short, but

illuminating visit to Hoxha’s heavily guarded stronghold. Some of my audience

are too young to remember life under the dictatorship, but those who are old

enough say that what I relate is only too painfully true. One gentleman, aged

about 45 and brought up in Albania ,

said after hearing one or two of my anecdotes:

“You must write these things down. No one

believes me when I tell about how terrible it was living in Albania

And, that is exactly what I’ve

done in my book Albania on my Mind.

My book is divided into two main

sections. The first deals with how I became obsessed with Albania , and

the second contains a collection of memories of the trip I made there in 1984.

My interest in the country began when I used to spend,

“…much of my spare time during my mid-teens haunting

second-hand bookshops.

In the

second half of the 1960s, Hampstead

Village Albania

My curiosity about Albania

was aroused. I needed to know more about this place, about which so little

information was available in the 1960s. Even today, not many people know much

about it.

As the years passed, I made numerous trips to places in the Balkans

from where I could catch a glimpse of the country which was beginning to

tantalise me. On one trip, I took a bus over the Cakor

Pass which links Kosovo with Montenegro . It traverses

the mountains shared by these places and Albania . When the bus stopped at

the top of the pass,

“…a grubby little

boy approached me. He said something to me in a language, which I did not

recognise as being Serbo-Croat. It was probably Albanian. Somehow, he made it

clear to me that he wanted foreign coins. I thought that he was either a

beggar, or more likely, just a curious youngster pleased to have chanced upon a

foreigner. I gave him a few British coins, and then he rummaged around in his

pocket. After a moment, he handed me a

few Yugoslav Dinar coins, and left. He was no beggar, after all, but simply a

young fellow with a well-developed sense of fairness.”

Although it was impossible to speak with Albanians in

Albania - contact between them and foreigners was strictly discouraged by the

authorities - I did manage to discover how friendly they are when I stayed in

Kosovo, the part of Serbia which has an enormous Albanian population. When I

disembarked at the bus station in the Kosovan town of Prizren sometime in the 1970s,

“…I was

immediately surrounded by people, mostly young men. Everyone wanted to know my

name, rather than my nationality or where I had come from. When I said it was

‘Adam’, they then asked me whether I was a Moslem. The answer did not seem to

matter to them; they were just pleased to meet a stranger.”

Contrast this with what happened within 12 hours of my arrival in Albania

in 1984:

“After lunch, the

Australian, who was travelling with us, called me aside, looking shocked. He told me that when he was in the hotel’s

lift, an Albanian couple began to strike up a conversation with him, but

stopped abruptly mid-sentence. It was, he felt, as if they were keen to speak

to an outsider, but became scared of the consequences of being caught doing so.

Maybe, they had been worried, not without reason, that the lift might have been

fitted with a hidden microphone.”

In fact, whenever anyone wanted to try to talk to us in

the country, they were warned against doing so by others standing nearby. Even

our Albanian guides were wary of what they said to us. We, the foreign

tourists, were regarded not only as guests (the guest is held sacred by

traditional Albanians), but also as potentially dangerous intruders from the

hostile world beyond Albania ’s

hermetically sealed borders. They were constantly keeping an eye on each other

as well as us.

My trip to Albania

was a truly remarkable experience. I am certain,

“…that the Albanians did not regard us as being

simple tourists, but rather as potential messengers. We were being shown the

country with a view, so our hosts hoped, to providing us with information that

we could use to broadcast to the world how well Albania was progressing along

the isolationist path it had chosen to take.”

I am not sure

that the message we took home was quite what the Albanians had hoped. We were

taken around a factory, of which our hosts were very proud. It purported to

make precision instruments, but,

“… the sliding (Vernier) calliper, which had been

made in the factory… was a crude object, whose jaw slid jerkily rather than

smoothly. The markings were badly scored and looked a little irregular.” ‘Precision’ it was not!

And, although the

Albanian-built tractor on display at an exhibition of Albanian industrial

products in Tirana,

“… differed in design from the Chinese

tractors that we had seen on our travels, we had not seen even one of these

home-made machines anywhere outside the exhibition.”

Nor, could I find outside the exhibition any samples of the

“…yellow plastic bunny rabbit holding a rifle in exactly the same

pose as the soldier, who had watched our arrival at the Albanian frontier.”

I would have loved to have bought one of these to protect my garden.

It is easy to criticise, but one must not forget to praise. Even if I

was unable to meet many Albanians on the tour I made in 1984, I cannot fault

our hosts on the care that they took to make sure that we were comfortable and

well-fed. Although their main interest appeared to be to ply us with propaganda

and to show us what they wanted us to see, they showed us a great cross-section

of their beautiful country.

I have not revisited Albania

since 1984, but would like to do so. Never in my wildest dreams in my younger

days did I imagine that I would now be able to slip out of my surgery, enter a neighbourhood

café, and then order a cappuccino from an Albanian barista. And, the

smile of gratitude, which I receive when I thank him by saying ‘faleminderit’

and shout ‘mir u pafshim’ when I leave, melts my heart. Even as I write

this piece, I realise that although many years have passed, I still have Albania

on my mind.

ALBANIA ON MY MIND is available in Kindle on Amazon web-sites

&

in paperback by clicking HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Useful comments and suggestions are welcome!